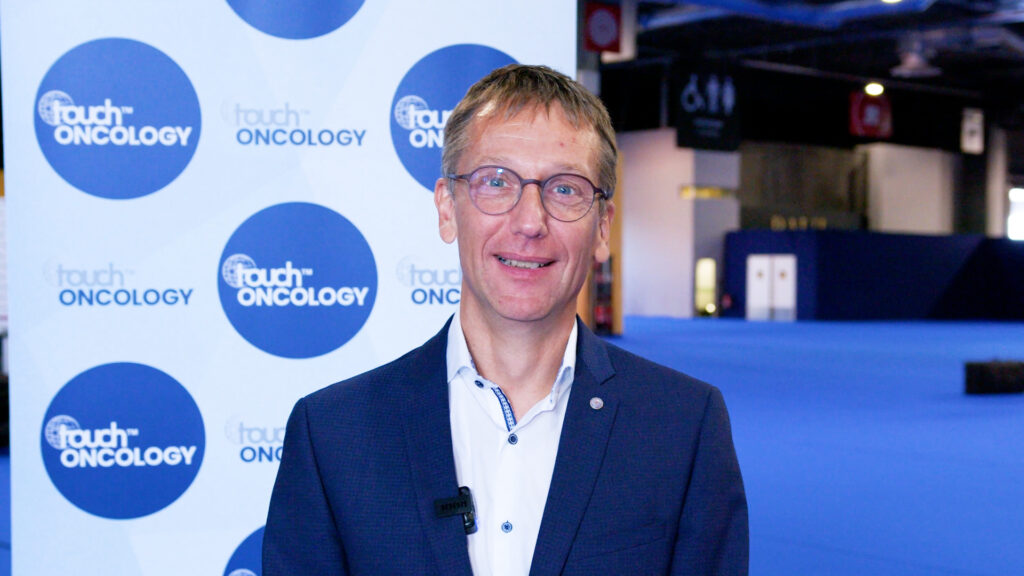

In this interview, Dr Michael K. Gibson (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA), an expert in head and neck and gastrointestinal (GI) oncology shares his personal journey, reflecting on how early experiences with cancer shaped his path. He discusses challenges in the rapidly evolving field of oncology, and his hopes for the future. His insights offer inspiration for aspiring oncologists and a vision for advancing cancer care worldwide.

In this interview, Dr Michael K. Gibson (Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA), an expert in head and neck and gastrointestinal (GI) oncology shares his personal journey, reflecting on how early experiences with cancer shaped his path. He discusses challenges in the rapidly evolving field of oncology, and his hopes for the future. His insights offer inspiration for aspiring oncologists and a vision for advancing cancer care worldwide.

Q1. Can you share a summary of your journey into the field of head and neck and upper GI oncology?

Sure, I think my path has been shaped by a combination of personal experiences, intellectual curiosity and chance opportunities. When I was younger – in middle and high school – I didn’t fully understand where life would take me, but personal interactions with cancer, including my grandfather’s experience with small cell lung cancer, had a profound impact. Watching how cancer affects individuals and families made me want to contribute in a meaningful way, to prevent others from experiencing similar pain. Looking back, I might even call it ‘a calling’ – a personal drive to make a difference, a chance to give back and finding fulfilment in helping others.

Initially, I was drawn to science simply because I found it fascinating. I wasn’t entirely set on medicine; I explored other paths, from political science to law. But I kept coming back to biology and its practical applications. During college at North Carolina State University, I had the incredible opportunity to work in the lab of Dr Kenneth Korach at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. That experience introduced me to research, basic biology and the thrill of publishing scientific papers as an undergraduate. It sparked my interest in combining science with practical impact, laying the foundation for my future career.

Medical school was another turning point. I was fortunate to attend Johns Hopkins, despite initial concerns about the financial burden. It was a decision I made with the encouragement of mentors who emphasized the long-term value of connections and education. Once there, I faced the challenge of figuring out my specialty. I took a year off to re-immerse myself in science by working in the lab of Curtis Harris at the National Cancer Institute. During this time, I considered residency in everything from dermatology to pathology (I even completed an autopsy pathology rotation), but ultimately returned to my “null hypothesis”: internal medicine. I’ve always been drawn to solving problems and making a direct impact on patients’ lives.

The next major pivot came during residency and fellowship, when I began gravitating toward oncology. A pivotal mentor, Prof Arlene Forastiere, was instrumental in shaping my focus on head and neck and oesophageal cancers. Her pioneering work and determination were deeply inspiring, and I admired her so much that I wanted to follow in her footsteps. During my fellowship, I also gained firsthand, practical experience in clinical research, working on a trial combining novel therapies with chemo-radiation for oesophageal cancer. This project was the applied clinical trial that I developed concurrently during didactic training in clinical investigation as part of my graduate studies at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Graduate Training Program in Clinical Investigation. This intersection of patient care, clinical research and science cemented my commitment to oncology.

On a personal note, staying in Maryland for my training turned out to be invaluable. My father was diagnosed with colon cancer during my fellowship and being nearby allowed me to be present for his care – a bittersweet reminder of why I chose this field. It was a difficult time, but it reinforced my dedication to improving outcomes for others facing similar battles. I might also add that the support of my family, in particular my wife Julie, is the bedrock of my career efforts.

Today, my career combines patient care, research and mentorship. I find meaning in balancing the emotional challenges of oncology with the hope and progress that research brings. Even when treatments fall short, research offers a way to channel frustration into action and innovation. It’s a career I feel grateful for every day, one that allows me to make a tangible impact while continuing to learn and grow.

Q2. Do you have any advice for young, aspiring oncologists?

If I were offering advice to someone considering a career in medicine, I’d start with perspective. For me, despite all the challenges and changes, I wouldn’t choose anything else. It’s a career that has given me purpose and fulfilment, and as the landscape shifts, adapting is part of the journey.

That said, medicine isn’t for everyone. It requires a lot of what others might consider “free time” to be devoted to learning, working and growing. You must ask yourself: does this bring you joy? Because if it doesn’t, you’ll struggle to stay motivated and productive. Finding a specialty or area that truly excites you is essential – it took me a while to figure that out for myself.

I also remind people that much of your journey will be shaped by mentors, opportunities and circumstances beyond your control. Success requires focus, resilience and the willingness to roll with the punches. Surround yourself with mentors who inspire and support you, stay committed to your goals and, above all, make sure you genuinely love what you do. That passion will carry you through the toughest moments.

Q3. Please summarize your current research interests

For a while I worked with head and neck cancers, but over time I realized I derived more satisfaction from working with stomach and oesophageal cancer. This is a great example of how your path in medicine can evolve as you grow and reflect. My mentor, Dr. Forastiere, specialized in this area, so in many ways it feels like I’ve come full circle.

Nowadays, I lead the upper GI translational research program, and am part of a GI oncology team of dedicated oncologists, all experts in their field. My role combines clinical care, research and collaboration, all of which align with my overarching goal: applying scientific principles to address unmet needs in oncology, always with patient safety and ethics in mind.

A big focus in oncology now is immunotherapy – it’s the buzzword of the moment. While it’s revolutionary in some ways, it’s not the cure-all many hoped for. Median survival for metastatic cancers has improved by just a few months, which is significant in our field but still leaves a lot to be desired. Only a fraction of patients benefit from this treatment, so our task is to figure out why and refine our approaches.

I collaborate with scientists who focuse on oesophageal cancer. My role involves obtaining and banking tissue samples from my patients, designing clinically relevant studies and exploring why treatments succeed for some and fail for others. Together, we try to identify actionable markers or pathways, test potential interventions in the lab, and eventually bring them into early-phase clinical trials. It’s a slow, iterative process, but it’s deeply rewarding.

Beyond research, I wear many hats. I’m involved in national and international collaborations, including a consortium with colleagues in Japan and Africa to study oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma – a cancer that’s rare here but prevalent globally, particularly in underserved regions. These collaborations allow me to expand my network and contribute to broader solutions while learning from diverse perspectives. Continuing participation in the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG-ACRIN) provides me with research stability and the opportunity to work with talented folks across the US.

I also mentor younger professionals, write papers and engage in administrative duties. Teaching and mentorship are my way of paying forward the support I’ve received throughout my career.

Q4. What is your vision for the future of gastrointestinal oncology advances in the next 10 years?

When I think about the future of gastrointestinal oncology over the next decade, I’m cautiously optimistic. While the reality of cancer care is often tainted by tough outcomes, I genuinely believe we’re making progress – and we have the data to prove it.

I tell my patients this often, especially when they ask the big-picture questions about cancer treatment. Take metastatic colon cancer, for instance. When my dad had it decades ago, the only drug available was 5-fluorouracil, and the median survival was about nine months. Today, the median survival is closer to three or four years, and people often live well during that time. Similarly, in oesophageal cancer, what was once a near-certain death sentence has evolved to offer cures and extended lives for many. These are enormous strides, both in terms of quantity and quality of life, and they give me hope that we’ll keep pushing forward.

The challenge lies in accelerating that progress. Research is advancing exponentially, with countless new therapies, targets and combinations being developed. That’s amazing – but it’s also overwhelming. We’re testing more drugs than ever, but the sheer volume of options makes it difficult to determine the best combinations and sequences. Clinical trials are inherently slow; the time it takes to design, run and analyze a study means that by the time results come in, the field may have already moved on.

How do we stay efficient and ensure patients benefit as quickly as possible? That’s a critical question for the next decade.

One promising direction is learning how to integrate targeted therapies and immunotherapies more effectively. We’ve seen success combining agents, like HER2-targeted therapies with immune checkpoint inhibitors, which can significantly extend survival in certain patients. But even that process has its limitations. For example, recent trials have shown that some therapies only benefit patients with specific biomarkers, such as a PD-L1 score above a certain threshold. Balancing science, ethics and practical constraints – like cost and patient access – is a constant struggle.

We also face tough decisions about equity and resource allocation. As much as we strive to provide every possible option to every patient, the reality is that healthcare systems are constrained by economics. Some treatments are simply too costly or the benefit versus the toxicity isn’t clear, and we must prioritize evidence-based care. Yet, we also need compassion for patients seeking hope, even in unproven or alternative therapies, especially when conventional options are exhausted.

Despite these challenges, I remain hopeful. Advances in drug discovery, artificial intelligence and clinical trial design give me confidence that we’ll continue to improve survival and quality of life for cancer patients. It won’t be easy, but with innovation, persistent effort, collaboration and hope, I believe we’ll eventually make cancer a manageable chronic condition – like how we transformed HIV care decades ago. That’s the vision that keeps me going.

Cite: A personal drive to make a difference: Dr Michael K. Gibson’s career in gastrointestinal oncology. touchONCOLOGY. November 27, 2024.

SIGN UP to touchONCOLOGY!

Join our global community today for access to thousands of peer-reviewed articles, expert insights, and learn-on-the-go education across 150+ specialties, plus concise email updates and newsletters so you never miss out.

Click here to REGISTER NOW >>>